In the fight for American independence, Frederick County, Maryland had a major part to play.

Here are the ways you can find the story of the American Revolution hidden in plain sight in Frederick, MD.

Native American Communities

In the millennia before Europeans landed on the shores of North America, the Monocacy River Valley was home to numerous Native American settlements, utilizing the forests, lands, and waterways of the region. Archeologists from the National Park Service at both Catoctin Mountain Park and Monocacy National Battlefield have documented the ways in which Native American communities employed the land in what became Frederick County, including quarrying stone from Catoctin Mountain and establishing settlements along the banks of the Monocacy River.

Colonial Fredericktown

In the early 1700s, English and Scots-Irish settlers began moving west from the shores of the Chesapeake Bay into the interior of Maryland. At the base of Catoctin Mountain and in the valley of the Monocacy River, colonists began establishing small farms. In the 1740s, an Irish businessman named Daniel Dulany received a land patent for 7,000 acres of Maryland countryside known as Tasker’s Chance. In 1745 he laid out a grid for a town that he called “Frederick-Town” in honor of Frederick Calvert, the 6th Lord of Baltimore.

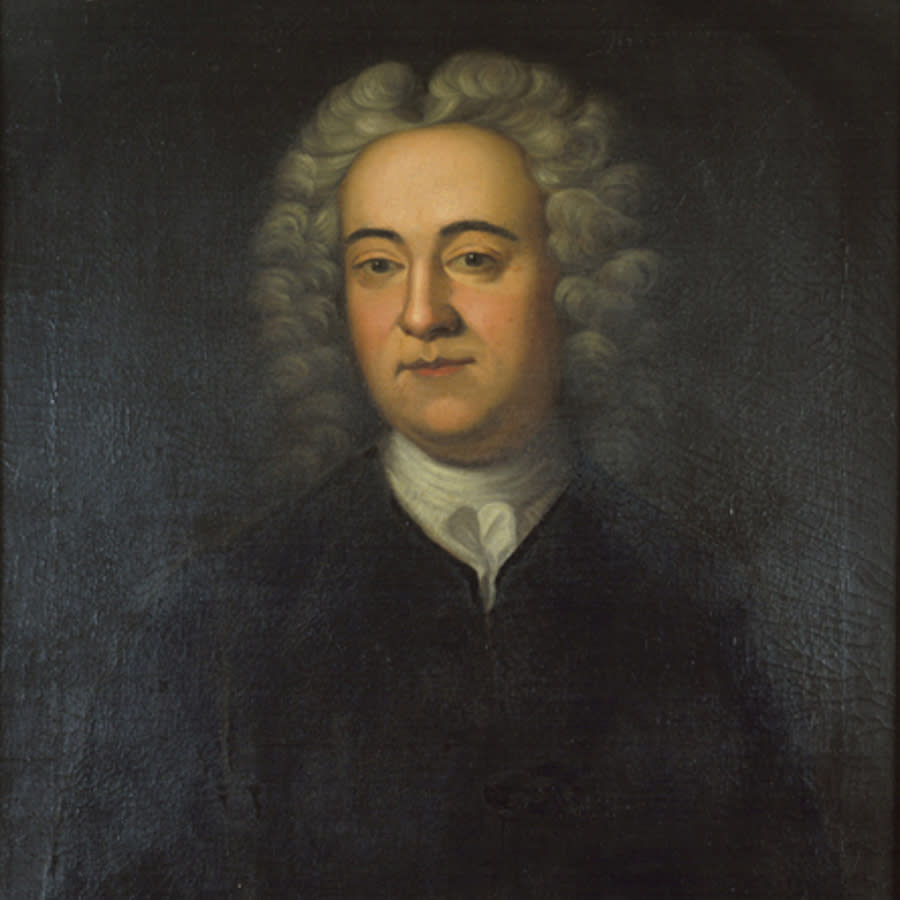

Daniel Dulany (Maryland State Archives)

Daniel Dulany (Maryland State Archives)

One of the ways Dulany intended to develop the land that officially became Frederick County in 1748 was by inviting German immigrants from Pennsylvania to settle in the Fredericktown area. Among the families that arrived were Josef and Catharina Brunner. They established a home along Carroll Creek they called “Schifferstadt.” Their original log cabin gave way to a large stone farmhouse in 1758. Today, you can visit Schifferstadt Architectural Museum and learn more about the building and the colonial era in Frederick.

Schifferstadt Architectural Museum

Schifferstadt Architectural Museum

A fateful meeting on the banks of Carroll Creek

As European colonists continued to pour into Maryland in the mid-18th century, conflicting land claims led to conflict not only between Europeans and Native Americans but between rival European nations. In 1754, war broke out between English and French forces in the Allegheny Mountains. The fighting quickly spread to become a global conflict known as the Seven Years’ War but known locally as the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

Fredericktown hosted an important meeting between three important colonial leaders in April 1755. In a small tavern near Carroll Creek in what is today Downtown Frederick, General Edward Braddock, Colonel George Washington, and Postmaster Benjamin Franklin met to coordinate the attack that Braddock planned on the French army’s Fort Duquesne near modern-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

General Edward Braddock, Colonel George Washington, and Postmaster Benjamin Franklin

General Edward Braddock, Colonel George Washington, and Postmaster Benjamin Franklin

Franklin allegedly warned General Braddock about the danger his army of British soldiers would face against highly skilled French and Indian forces. Braddock arrogantly replied:

“These Savages may indeed be a formidable Enemy to your raw American Militia but upon the King’s regular and disciplin’d Troops, Sir, it is impossible they should make any impression…”

Postmaster Benjamin Franklin and General Edward Braddock meeting in 1755

Postmaster Benjamin Franklin and General Edward Braddock meeting in 1755

Three months later, in the Battle of the Monongahela, General Braddock was killed in battle leading a disastrous retreat from Fort Duquesne. Braddock failed to heed Ben Franklin’s sage advice during their meeting in Fredericktown.

While the tavern where Braddock, Franklin, and Washington met was torn down in the early 1900s, you can visit the site of the meeting on Carroll Creek Park just west of Court Street. A plaque marks the location and it is connected to the rest of Downtown Frederick via Carroll Creek Park.

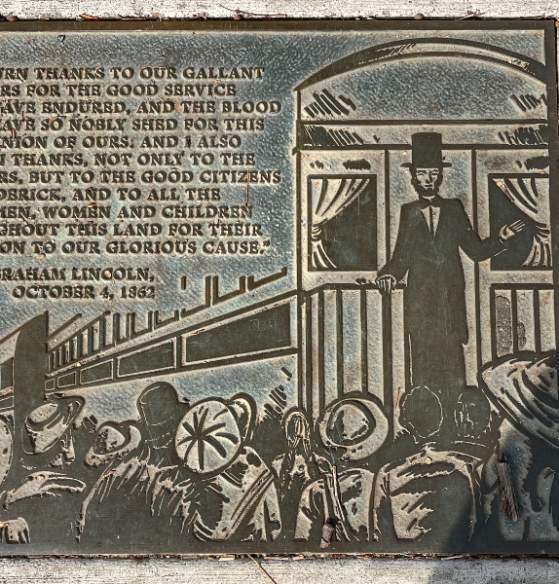

Historic marker near the tavern site on Carroll Creek Park

Historic marker near the tavern site on Carroll Creek Park

Repudiating the Stamp Act

The British achieved victory in the French and Indian War in 1763. But the conflict planted the seeds of a future war. In order to pay down the debts accrued by the British Crown in the conflict, heavy taxes were placed on goods in Great Britain’s American colonies, including Maryland. Among these taxes was the infamous Stamp Act of 1765.

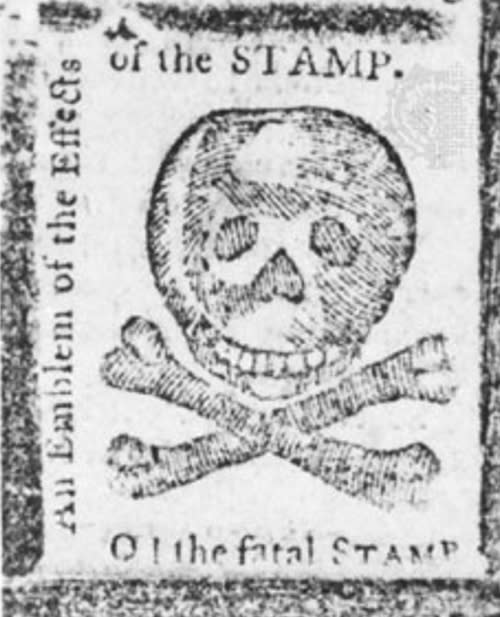

"O! The Fatal Stamp" - A political cartoon opposing the Stamp Act of 1765

Frederick became the first community in the colonies to formally protest the Stamp Act, which placed a tax on legal documents and printed material. Twelve judges in Frederick County repudiated the Stamp Act on November 23, 1765, refusing to require local residents to use stamped papers during a meeting held in a home on Record Street near the county courthouse.

A week after the judges acted, a crowd in Fredericktown held a mock funeral where they buried a copy of the Stamp Act and an effigy of a royal tax collector on the grounds of the county courthouse, now home to Frederick’s City Hall. In the months that followed, protests against the Stamp Act took place in communities throughout the colonies. The events that started at Frederick were the first in a series that led toward Revolution.

Today, you can visit the locations where the Stamp Act protests and Repudiation took place. A wayside marker in the park at City Hall tells the story of the judges’ actions and the protest that took place on the grounds in November 1765. Until recent years, Repudiation Day was marked as a holiday on November 23rd in the State of Maryland in commemoration of the events in Fredericktown.

You can find this wayside adjacent to City Hall, the former home of the Frederick County Courthouse.

You can find this wayside adjacent to City Hall, the former home of the Frederick County Courthouse.

Supplying an Army

When Revolution broke out and war commenced in 1775, a decade after Frederick’s judges repudiated the Stamp Act, the growing community in Frederick County was largely spared the devastation seen in areas of New England, Pennsylvania, and parts of the Southern colonies.

The county sent hundreds of men to fight for independence with Maryland regiments in the Continental Army. On the home front, a new industrial operation opened at the base of Catoctin Mountain in northern Frederick County.

The Johnson family opened an iron furnace in 1776. As the Revolutionary War dragged on, the Catoctin Furnace manufactured iron products for local farmers and stoves for Frederick County residents, but the Johnson brothers eventually ordered the construction of cannon balls for General George Washington’s forces to use during the Siege of Yorktown in 1781.

The remains of Catoctin Furnace are preserved today by Cunningham Falls State Park

The remains of Catoctin Furnace are preserved today by Cunningham Falls State Park

To manufacture these weapons in the fight for freedom, the Johnson brothers paradoxically used slave labor. Enslaved men and women worked the furnaces and in the village that supported the iron-making operation. The furnace continued operation using enslaved labor until the 1840s and remained in use until 1903.

Discover Black history in Frederick County HERE

Today, you can visit the historic furnace and the village of Catoctin Furnace. The Catoctin Furnace Historical Society and their Museum of the Ironworker tell the story of the enslaved workers who lived and died in the village, the Johnson brothers whose fortune was made in iron, and the iron furnace that helped build a new nation.

Forensic facial reconstructions at the Museum of the Ironworker tell the stories of two enslaved people held in bondage at the Catoctin Furnace

Forensic facial reconstructions at the Museum of the Ironworker tell the stories of two enslaved people held in bondage at the Catoctin Furnace

You can also learn more about the Johnson family and visit one of their historic homes. Rose Hill Manor, operated by Frederick County Parks and Recreation, is a park and museum that tells the story of Thomas Johnson who went on to become the first governor of the State of Maryland, and his farm.

Rose Hill Manor Park was the post-Revolutionary home of Thomas Johnson

Rose Hill Manor Park was the post-Revolutionary home of Thomas Johnson

Housing Prisoners of War

As the Revolutionary War raged in the 1770s, construction began on barracks to house equipment for the Frederick County militia. Two L-shaped stone buildings and a parade ground were planned on a site occupying a hilltop on the southern side of Fredericktown.

The grounds adjacent to this building (unfinished as the American Revolution raged) served a different purpose during the war.

The grounds adjacent to this building (unfinished as the American Revolution raged) served a different purpose during the war.

However, before the construction could be completed, the site became a make-shift prisoner-of-war camp for British and Hessian soldiers captured by the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

Because many residents of the Frederick area were German, some of the Hessian mercenaries held at the camp later settled in Frederick County. Among those who did so was Johannes Conrad Engelbrecht. His grave can be found today at the small cemetery adjacent to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Downtown Frederick.

The grave of Johannes Conrad Engelbrecht can be found on 2nd Street in Downtown Frederick.

The grave of Johannes Conrad Engelbrecht can be found on 2nd Street in Downtown Frederick.

The Hessian Barracks where Englebrecht and his comrades were held later served as a storehouse for the local and state militia, a warehouse for supplies for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, a Civil War hospital, and finally, a building on the campus of the Maryland School for the Deaf as it remains today. One of the original L-shaped buildings survives today, and historical placards tell the incredible story of these historical buildings constructed as the War for Independence raged.

The Hessian Barracks stood on ground now included on the campus of the Maryland School for the Deaf

The Hessian Barracks stood on ground now included on the campus of the Maryland School for the Deaf

These are just a few of the many places where you can explore American Revolutionary history in Frederick County. Visiting these locations, you can feel the sense of place, those important events that happened here, shaped by the people who created the United States of America.

These stories are connected to much larger stories in our national history by several historic by-ways that pass through this region of Maryland. Check out the Historic National Road and Journey Through Hallowed Ground scenic byways to explore how these Frederick County stories connect to our nation’s history, from the American Revolution to the Civil War to our own time today.

Black History and Culture

Explore the stories and contributions of Frederick County's African American communities.

Float Through History

Grab the kayak or canoe and head for the Monocacy River to find Frederick's history.